Lipa

CZ/ENGWhat Happened In This Place?

The mountain village of Lipa is not far from the border with Slovenia. A tragedy was written into Croatian history there on April 30th, 1944. On that day, German and Italian troops stormed into the village, the entire surrounding region of which had been occupied after the Italian armistice in 1943. This was how operation “Braunschweig” started. It was directed at numerous groups of partisan fighters, who were hiding in the surrounding forests. The operation amounted to the attack and liquidation of the civilian population. In this way, the region was supposed to be “cleansed” of partisans. Almost all of the inhabitants found in the village around noon that day were killed. In total, 269 people died, including 96 children. The majority of the population of Lipa was burned alive in a building called the “Kvartirka.” Afterwards, the entire village was burned down.

How Does This Place Look Today?

Reminders of the tragic events naturally pervade everyday life in present-day Lipa — though if not for the preserved ruins of houses in the center of the village opposite a small building with a museum, the spot would not be any different from the other villages in the region. Here, though, a museum with the official name of “Memorial Center Lipa Remembers” reminds people of the fate of Lipa’s inhabitants. It was opened in its current form in 2015 on the location of the original museum, which was open from 1968 – 1989. The building is maintained by the Maritime and History Museum of the Croatian Littoral in Rijeka, and it is remarkable mainly for its interesting architectural design.

The original memorial on the edge of the village also commemorates the events of April 30th, 1944 in Lipa. This was created through the initiative and personal resources of the survivors in 1953, on the spot of the building where the majority of Lipa’s population was murdered. Along with five-pointed stars from when it was originally built, there are also memorial plaques with names and photos of the victims. After the breakup of socialist Yugoslavia, a cross with a picture of Jesus Christ was added.

Both of these places are located right on the main road that goes through the whole village. The original cobblestone paving was recently replaced with asphalt during recent repairs. In the areas in front of the museum and memorial, though, the cobblestones were deliberately kept. This forces the majority of the cars going through to slow down. The driver is thus supposed to realize that he’s passing through a place with a troubled history.

What does this place serve as?

Lipa isn’t far from the big port city of Rijeka, but in the present day it’s rather ignored. During the Yugoslav times, bus tours full of people came every day, but now there are only a few school groups every year. There also aren’t many individual visitors. This lessened interest in Lipa is because of a change in the culture of remembrance that has taken place in Croatia since the breakup of Yugoslavia. Events from the recent war of independence are remembered rather than the history of the Second World War. The museum here, though, has greater significance for the local inhabitants. The Memorial Center Lipa Remembers also serves as a community center and a place of official and everyday gatherings. They regularly hold various social and cultural events there.

What is (not) remembered here?

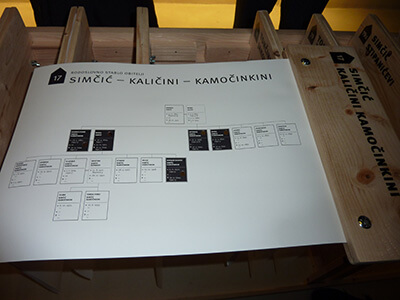

The permanent exhibit doesn’t just focus on the tragic events of 1944, but also on the years and centuries that preceded them. The region’s history, right from its first settlement, thus comes up as the themes of the individual sections of the exhibit. It particularly emphasizes local customs and the traditional way of life, which completes the ethnographic collection exhibited there. Only one of the three parts of the museum, set in a dark area with black walls, deals with the events from 1944. The central element of this section is a long line of family trees of the families from Lipa, organized by the addresses of the individual homes. The victims of the Lipa massacre are marked on the family trees. On the opposite wall, there are small models of the homes with the addresses, the names of the family, and the birthdates of the family members who were murdered. The victims, then, have only a scant entry on a list. Visitors can create their own image of the victims’ age and their familiar relationships, thus better understanding the scale of this tragedy.