Jasenovac

CZ/ENGWhat Happened In This Place?

At the Jasenovac concentration camp during the reign of the Ustaše-led Independent State of Croatia, more than 83,000 people brutally lost their lives. By 2013, 47,627 murdered Serbs, 16,173 Roma, 13,116 Jews, 4,255 Croats, 1,128 Muslims, 266 Slovenes, 114 Czechs, 106 Slovaks, and 205 victims of other nationalities had been counted. Partisan units freed the camp in 1945. An intensive, organized liquidation of the prisoner population had been carried out in the months before the camp’s liberation, though, so there wasn’t anyone left to save. The Ustaše themselves partly destroyed the camp during the war. Now, only a few outlying buildings that were part of the camp complex remain. Ruins of the remaining buildings that stand in the area of the memorial today were taken apart after the war and used to repair damaged homes.

How Does This Place Look Today?

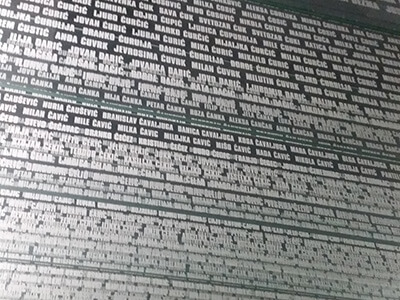

At the site of the former concentration camp complex, specifically camp no. 3, which was nicknamed “the brickyard,” you can now find the “Stone Flower” memorial, by sculptor Bogdan Bogdanović. This concrete statue was built in 1966 as part of a memorial to the victims. The flower isn’t supposed to bring to mind death and killing, but rather the opposite: life and rebirth. Besides the concrete flower, two adjacent ponds also occupy the area of the memorial. The ponds are separated from each other by a path lined with wooden railway ties that prisoners traveled over on their ways to Jasenovac. The places where the individual buildings of the camp once stood are marked with depressions in the landscape. The spots that were used for torturing and murdering prisoners are now artificially created hills. The memorial at Jasenovac was founded in 1963, and a museum was opened about five years later. The current exhibition is from 2006, and it’s divided into one section dedicated to the victims, and another to the perpetrators. In the first of these, we find surviving personal effects and lists of the victims’ names. In the second section, the exhibition has, for example, Ustaše decrees against Serbs, Roma, and Jews, or tools that camp prisoners were killed with.

What Does This Place Serve As?

The memorial and the museum aim to mark the events that took place here during the Second World War. An education center, which offers various programs for schools, is also part of the complex. A visit to Jasenovac, however, is not a mandatory part of the school curriculum, and most only come because of individual educators’ personal initiative. In the last year, 12 school field trips visited this place. You can say that in comparison with other Croatian places of memory, Jasenovac is given disproportionately little attention. This fact can be understood as a result of the political controversy involving the ethnic and racist overtones that play out in the space of the former Yugoslavia. Acts of reverences also take place at the memorial, attended by survivors of the victims and political representatives.

What Is (Not) Remembered Here?

The core of the controversy surrounding Jasenovac is the fact that various actors within the post-Yugoslav space have long used the historical narratives connected with it for political agitation. During Josip Broz Tito’s socialist regime, they made a memorial with an anti-nationalistic character. After the split with Stalin in 1948, however, the regime extracted itself from the Soviet sphere of influence, but the government still could not talk about democratic conditions or upholding human rights. Even until today, Jasenovac can be seen as a symbol of Croatian historical revisionism and the relativization of racism and xenophobia — and the violence which that resulted it — for many Serbs, Roma, and Jews in the region. Its image was even used this way during the war in the 1990s, as an excuse for the national-nationalist direction of Franjo Tuđman’s government and the comparisons between the newly independent Croatia and the wartime Independent State of Croatia. Now, the main points of controversy are the dispute over the number of victims, the character of the concentration camp, the living conditions of the prisoners, and also the question of whether the camp was used by the Tito regime as a political prison even after its liberation. The Croatian government and representatives of the local Jewish community and Serbian Orthodox church all publicly venerate the site every year, but the acts of reverence still take place separately.